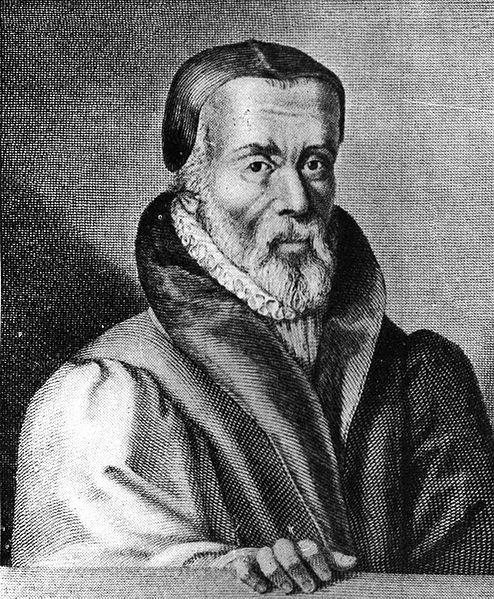

William Tyndale was an extraordinary pioneer. His Bible translation, although never finished, was the first of the modern English translations, the first English translation to be done directly from the Hebrew and Greek, the first to take advantage of the new printing technology.

Perhaps these pioneering steps don’t seem so remarkable today, in the age of computers, space travel and MRIs. Consider for a minute the context of Tyndale’s life.

Perhaps these pioneering steps don’t seem so remarkable today, in the age of computers, space travel and MRIs. Consider for a minute the context of Tyndale’s life.

After Wycliffe’s fourteenth century translation had been completed and gained immense popularity, the translation of vernacular Bibles – Bibles translated in a way ordinary people could understand – was banned as heretical. Almost all English Bibles were burnt. In 1519, while Tyndale was at Cambridge University, Foxe records the deaths of seven people, burnt for teaching their children the Lord’s Prayer in English.

When challenged by a clergyman in this context, Tyndale said he was determined that ‘If God spares my life, ere many years, I will teach the boy that driveth the plough to know more of God’s laws than thou dost.’ And he probably did.

The beginning of the Gospel of John. Photo by Kevin Rawlings.

In 1524, Tyndale left England for Wittenburg and began this translation of the New Testament. The following year, the first attempt to publish was halted, but it was completed in 1626, first in Worms and later in Antwerp. The copies were smuggled into Scotland and England. Soon they were banned: warnings were issued to booksellers not to consider selling them and many copies were publically burnt. Although Tyndale had expected furore, he was shocked: the first edition contained only translation, without commentary or notes against which to protest. They were burning the word of God.

In January 1529, Tyndale was publically declared to be a heretic. It was in the same year that he revised the New Testament and started the Old. Nothing would deter him from his aim, and his single, persistent plea was that the king would permit the translation. He did not.

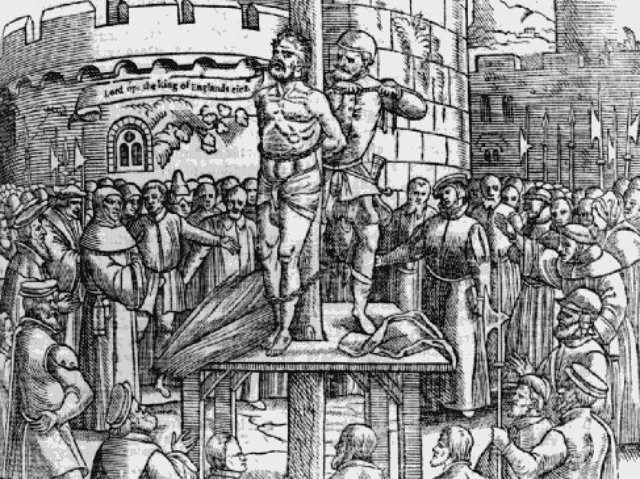

On this day in 1535, a young man called Henry Phillips, whom Tyndale had taken into his trust, betrayed Tyndale as they were walking through the streets of Antwerp. Tyndale was imprisoned, tried, strangled at the stake and his body burnt. With his last recorded words, he asked God to open the King of England’s eyes.

On this day in 1535, a young man called Henry Phillips, whom Tyndale had taken into his trust, betrayed Tyndale as they were walking through the streets of Antwerp. Tyndale was imprisoned, tried, strangled at the stake and his body burnt. With his last recorded words, he asked God to open the King of England’s eyes.

Within four years of that cry, the same king encouraged the publication of four English translations. All, like many translations since, were based on Tyndale’s work. Even the monumental King James Version is estimated to be between 75 and 85% Tyndale’s. It has been said that Tyndale ‘is the mainly unrecognised translator of the most influential book in the world. Although the Authorised King James Version is ostensibly the production of a learned committee of churchmen, it is mostly cribbed from Tyndale.’ (Joan Bridgeman)

When we sing of Jehovah, we use Tyndale’s word. When we say that 1 Corinthians 13 is ‘the love chapter’, we use Tyndale’s word. The same is true when we speak of…

- Passover

- Scapegoats

- Fighting the good fight

- It came to pass

- Let there be light

- The twinkling of an eye

- Or salt of the earth.

Many of the world’s ploughmen don’t have access to God’s word. More than 350 million people speak languages into which translation is yet to begin. Pioneer Bible translation.

- Go to blog homepage.

- Go to main Wycliffe Bible Translators UK homepage.